Sunday, February 28, 2010

100 bin prezervatif 14 günde bitti!

Saturday, February 27, 2010

Velodramatic's iPad App

Lots of cyclists, including us, are already thinking about iPad apps and a handlebar mount. Velodramatic photoshopped a mount and jokes in a post about the Colossus app.

Wind tunnel testing has shown that the low profile iPad has impressive drag numbers despite its size. Deda has fabricated several prototype stems with a revolutionary vacuum mount that channels low pressure behind the headtube via a specially ported fork. Amazingly the vacuum is strong enough to secure the unit on the worst pave Belgium has to offer. Perhaps we’ll see it make it’s first race appearance at Paris Roubaix if it passes the UCI’s technical review.

We don’t know about the viability of the iPad on handlebars and get the joke, but also expect a messenger bag or quick-access pannier for travel and again see the dashboard potential for touring and randonee; especially when connected to the Reecharge system.

Hungarian Bike to Work Campaign

If there were a World Championship for Promoting Cycling Positively, the Hungarians would be the bookmakers favourites to win every time.

There's simply very little competition out there to compete with them. The Dutch would be the only real competitors. Even so the Hungarians would probably win by a spoke simply because they're working towards increasing urban cycling and estabishing a bicycle culture and that energy would put them over the line first.

The above film is for the national Bike to Work campaign - Bringázz a Munkába. Showing cycling as normal and accepted. Highlighting community. Here's another one from the same campaign, showing what many might consider to be an unlikely candidate for cycling to work enjoying his commute. Selling it positively:

The Hungarian Cyclists Federation - Magyar Kerékpárosklub - are legends at promoting cycling positively. I've had the pleasure to meet with them and discuss promotion and behavioural campaigns. They are extremely well-informed and passionate and just sitting around a table with them is infectious. Their focus is, rightly, on mainstreaming urban cycling. Reestablishing the bicycle as a respected transport option. Respecting the sub-cultural aspects but aiming high at getting regular citizens to ride. For more about that there's always the Behavourial Challenges for Urban Cycling essay.

Here's another film from the campaign. We have enough Hungarian readers on this blog to be able to muster a translation, don't we? Chuck 'em into the comments.

And here's an advert from a previous Bike to Work campaign:

Rest assured, there are other cities doing the right thing and investing in campaigns that portray urban cycling for what it is; quick, effortless, enjoyable, etc. We have a few of them in this post about How Other Cities are Promoting Cycling.

But then there are cities who haven't understood the marketing basics. Like the last film in the above post about other cities, or the laughable attempt at 'promoting' cycling from Los Angeles DoT.

If we're talking World Championships, with the prize being a sharp rise in the number of Citizen Cyclists, cities that promote cycling with fear myths and car-centric angles won't even finish the race while cities like Budapest et al will win all the amazing societal benefits to be won.

I've been toying with the idea of a series of Copenhagenize Heroes photos. Portraits of people I've been lucky enough to meet on my bicycle travels and who inspire me and Copenhagenize. Let's start tout suite.

Copenhagenize Hero #1 - Janos Laszlo, President of the Hungarian Cyclists Club. For his undying optimism, passion and visionary goals for putting the bike back into Hungary, under the bottoms of Citizen Cyclists across the land.

Jpeg'den font bulmaca...

Sonra acaba doğru mu diye kendi kendimi yemek yerine...

http://new.myfonts.com/WhatTheFont/

Şahane jepg veriyorsunuz fontu tahmin ediyor.

Yeni İzmir’in ilk ‘mülk’ sahipleri

Tasarım Harikası(!) Modern mimarı(!)Güvenilir(!)Fonksiyonel(!)

Güngör, binanın arka tarafına 164 basamaklı, 8 kat merdiven yaptı. Binaya ulaşmak için 8 kat merdiven tırmanan apartman sakinleri, asansörü bulunmayan binada oturdukları kata da yine merdiven çıkarak ulaşmak zorunda kaldı.

Piriçelebi Mahallesi’nde inşa edilen 8 katlı ve 50 daireli apartmanın giriş kapısının bulunduğu tarafta yer alan arsaların sahipleri ile firma arasında anlaşmazlık çıktı. Anlaşmazlık tüm çabalara rağmen giderilemeyince Rizeli müteahhit benzeri pek görülmeyen bir uygulamaya gitti.

Yakup Güngör, binanın arka cephesine 8 katlı ve 164 basamaklı bir merdiven inşa etti. 40 dairesi dolu olan apartmanda oturanlar da ister istemez bu sıkıntıyı çekmeye mahkum oldu.

Binanın kaya zemin üzerine oturtulduğunu ve çok sağlam olduğunu belirten müteahhit Güngör ise, “Binanın asıl yolu arazi anlaşmazlığı nedeniyle yapılamadı. Bunun üzerine çare olarak arka bölüme 8 katlı bir merdiven inşa ettik. Bina sakinleri şimdilik bu merdiveni kullanarak binaya çıkacak. İleride arazi sorununu aşarsak araç yolunu yapacağız. 8 katlı merdiven bölümüne bir asansör yapmak için de araştırmalara başladık” dedi.

Herkez mutlaka okumuştur bu haberi ancak bir de burada ele alınması gerekir diye düşündüm..

Eklenmiş İmajlar

City: Rediscovering the Center

University of Pennsylvania Press has done a great service by reprinting William H. Whyte's classic text City: Rediscovering the Center. I consider this book to be part of the core of the American urbanist canon, alongside Death and Life if Great American Cities, A Pattern Language, and The City in History.

University of Pennsylvania Press has done a great service by reprinting William H. Whyte's classic text City: Rediscovering the Center. I consider this book to be part of the core of the American urbanist canon, alongside Death and Life if Great American Cities, A Pattern Language, and The City in History.William Whyte was the foremost empiricist of cities in the 20th century. He sought to turn the planning and design process on its head - to start with detailed observations of how the smallest scale of an urban place is used by people and work outward from there, designing places and writing codes accordingly. City: Rediscovering the Center begins with lessons drawn from sixteen years of meticulously recording plazas, streets, small parks, and marketplaces with time-lapse video and scientifically parsing out the patterns of behavior. Once the basic observations of human nature have been identified, he launches into an evaluation of the health of downtowns in their entirety.

What jumps out right away from Whyte’s study is the attention he pays to the most basic human needs. How does the provision of food impact the life of a place? Where do people use the bathroom? How can one find light on a cool day and shade on a sunny day? In other words, he doesn't travel very far up Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which I find to be a refreshingly humble and practical disposition toward the power of physical space in our lives. He never reaches for transcendence by design; that’s reserved for what happens in these places.

This leads to Whyte’s most important insight of all, one that really underscores each chapter of the book, that is: people want to be around other people. We are inherently social beings. As simple as this insight seems, it actually ran head on against the prevailing notion in planning at the time that people want as much space for themselves as possible. Whyte noticed that not only did friends clump together when sitting in a plaza, but even strangers tended to take seats in reasonable proximity to each other rather than evenly disperse themselves throughout the space. Well-used places were safer, both in perception and reality. People who stopped for conversation on sidewalks would typically not step out of the way, preferring to be in the center of movement. Parks and sidewalks that were outsized for their activity tended to swallow up its life and repel visitors. People like to be crowded, but not too much.

This leads to Whyte’s most important insight of all, one that really underscores each chapter of the book, that is: people want to be around other people. We are inherently social beings. As simple as this insight seems, it actually ran head on against the prevailing notion in planning at the time that people want as much space for themselves as possible. Whyte noticed that not only did friends clump together when sitting in a plaza, but even strangers tended to take seats in reasonable proximity to each other rather than evenly disperse themselves throughout the space. Well-used places were safer, both in perception and reality. People who stopped for conversation on sidewalks would typically not step out of the way, preferring to be in the center of movement. Parks and sidewalks that were outsized for their activity tended to swallow up its life and repel visitors. People like to be crowded, but not too much.Whyte’s design principles are simple and flow naturally from these foundations:

- People want places to sit. Steps are the best way to provide this, and there are specific proportions that can either encourage or detract from their use. Movable chairs offer a flexible counterpart to steps, and they won’t get stolen if they are cheap enough and locked up at night.

- People want things to look at. Storefront facades have to be designed to pull in onlookers with entrances that form a seamless transition between the street and building. It’s good for business and good for the city. Street trees, the larger the better, are terrific implants of nature into the heart of the city. Playful art is the best public art.

- Exclusion leads to unintended consequences. Impromptu street theater and music, illegal vendors and eccentric characters all add to the life of the street rather than detract from it. Attempts to discourage “undesirables” (his name for the indigent population), such as using spikes to prevent sitting, end up making the place inhospitable to everyone. Defensive enclosure does more to keep criminals in and well-hidden than it does to keep them out.

- Places are used differently at different times. Because of the movement of the sun, outdoor places will be used more during different times of the day depending also on the season. The city should protect its light from tall and wide buildings, but buildings can also be used to reflect light if placed well. The cycle of the traditional work day and home life will dictate the primary hours of use.

- Places need ongoing management. Although most people will walk a reasonable distance before throwing away trash, there will always need to be regular cleaning. Special events should be arranged, particularly to fill in time slots that are underutilized.

- Separation of vehicles and pedestrians usually favors vehicles. Skywalks and underground concourses force pedestrians either up or down a level and can suck the life out of a street. They can be useful in cold climates, but only as a complement to the street. Pedestrian malls are usually too wide or too long to be successful.

Remarkably, he happens to get almost all of his predictions correct (at least in my opinion):

- He notes the “corporate exodus” to the suburban office park in the 80’s but insists that the most creative firms will still not be able to live without the vitality and constant interactions of the city.

- Five years before Joel Garreau wrote Edge Cities, Whyte describes the phenomenon with at least as much precision and insight. He calls them “Semi-cities” (I'm not sure why the strange term “edge city” was the one to stick). He predicts that they will need to be shaped into the form of a traditional town, with a strong center and opportunities for walking. This is exactly what Tyson’s Corner is moving toward now.

- He compares the two transit movements of the 80’s: light rail and the people-mover. He sees much promise in light rail, but not people-movers. He considers the overhead structures to be cumbersome. When was the last people-mover installed?

- He forsees the predictions that communication technology will bring about the “the new geography,” allowing everyone to living in isolation in the suburbs or rural areas. He concludes that face-to-face contact will be as necessary as ever. This decentralization forecast was popular in the 90’s but reality has gone the opposite direction.

- He warns against downtowns competing with the suburbs on suburban terms, by building self-enclosed megastructures in the heart of the city. He tells cities to play to their strengths of street life and integration.

- Well before The High Cost of Free Parking, Whyte points to parking as the single most destructive force in the life of cities. He advises municipalities to switch from requiring it in large amounts to limiting it and allowing the highest and best use for downtown parcels.

Wednesday, February 24, 2010

Underwater Archeology: Diving 800 Feet Below an Ancient Cathedral

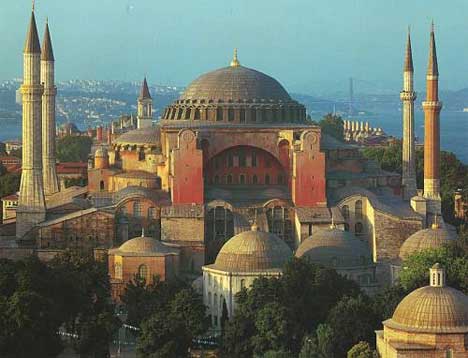

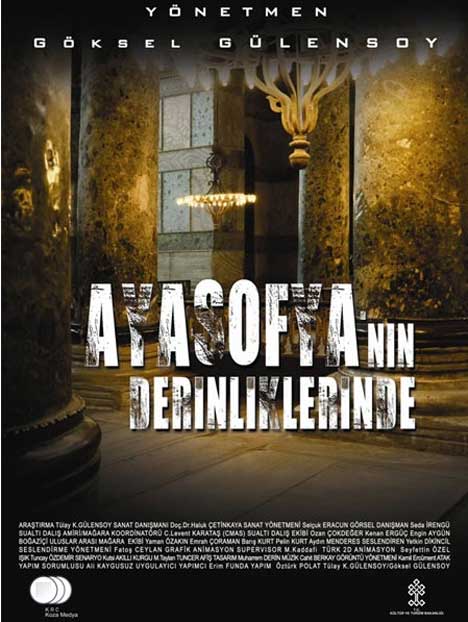

One of the oldest and largest cathedrals in the world hid a fantastic secret for centuries, one that was often rumored but not confirmed. The vast, splendid Hagia Sophia, which is now a museum, sits atop an ancient series of underground tunnels said to connect the cathedral with the Basilica Cistern, Princes’ Islands and Topkapi Palace. Director Göksel Gülensoy has enjoyed a long-standing love of the Hagia Sophia, and he decided to embark on a scuba diving expedition under the building to unlock some of her ancient secrets.

Gülensoy began his documentary project in 1998, but budget concerns and Turkish government red tape delayed its completion until late 2009. His 50-minute film, “In the Depths of Hagia Sophia” (or “Ayasofya’n?n Derinliklerinde”) shows a side of the historic structure that has never before been explored in depth, let alone filmed. Along with two divers and four spelunkers, the director delved into the mysterious depths to see what, exactly, Hagia Sophia was hiding.

The team began by opening the reservoir doors in the main hall; the two doors had both been shut for quite some time, and never before had a diver been allowed into the reservoir. After studying the small first chamber, the team moved on to the larger second reservoir. There they found flasks thought to have been left behind by British soldiers in 1917, a chain which may have contained a prisoner at one time, and various other bits and pieces of the cathedral. The spelunkers then took over and moved into the two passageways beneath the Hagia Sophia.

Beneath the huge cathedral, the team found sealed passages, a graveyard full of children’s bones, and the burial chamber of Hagia Sophia’s first priest. Threats of gas leaks, landslides and collapses weighed heavily on everyone’s minds, but the entire team emerged safely. For their own peace of mind, and to head off any rumors that might arise in the future, every person who dove beneath Hagia Sophia that day underwent a full-body X-ray to prove that no artifacts had been removed from the site.

After the project, it became clear that Gülensoy and his team had disproven many of the myths surrounding the ancient cathedral. The passages long thought to lead to the Basilica Cistern and Princes’ Islands were found to be nonexistent. However, the exploration led Turkish officials and the Hagia Sophia Museum Director to believe that further research should be carried out to see what other mysteries may be hiding beneath this beloved building. If he can gain the necessary government permissions, Gülensoy plans to return to make another film about the hidden history of Hagia Sophia.

Want More? Click for Great Related Content on WebUrbanist:

Underwater Cities, Ruins and Other Urban Archeology: 7 Submerged Wonders of the World

Some have even caused scientists to question the history of human civilization.

133 Comments - Click Here to Read More »»

8 Remarkable Palace, Fort and Castle Hotels: Living it Up in (Ancient) Luxury Around the World

Imagine curling up in front of an 800 year old fireplace where a king once rested (or was arrested!).

7 Comments - Click Here to Read More »»

79 Unique and Awesome Underwater Sculptures

Here are 79 unique and awesome underwater sculptures, environmental art in an underwater sculpture park, to encourage the natural ecological process.

3 Comments - Click Here to Read More »»

[ WebUrbanist - By Delana in Architecture & Design, History & Factoids, Travel & Places. ]

Representing and Understanding the City Graphically

Columnist Jeanne Haffner goes hands-on to learn how graphic representation is used in the day-to-day work of planning.

"

Sunday, February 14, 2010

Autodesk Çevrim içi Yeşil Bina Oyununu Piyasaya Sürdü

Emergent Urbanism, or ‘bottom-up planning’

I was asked to write an article around ‘bottom-up planning’ by Architectural Review Australia a while ago. It was published in the last issue, and I’m re-posting here. ‘Bottom-up’ is hardly the most elegant phrase, but I suspect you know what I mean. Either way, I re-cast it in the article as ‘emergent urbanism’ which captured a little more of the non-planning approaches I was interested in (note also the blog of same name, which I didn’t know about beforehand).

It partly concerns increased transparency over the urban planning process but also, and perhaps more interestingly, how citizens might be able to proactively engage in the creation of their cities. While it applies to Australian cities most closely, I hope the ideas here might be more generally interesting.

And for those of you outside Australia, there are a few subtitles required to read this. The ‘iSnack 2.0 debacle’ refers to Kraft’s unbelievably wrong-headed approach to ‘crowd-sourcing’ (sort of) a new name for a new cheesy derivative on the legendary Vegemite spread - more here.

And regarding this broad idea of emergent urbanism, a particularly inspirational recent project over this way has been ‘Renew Newcastle’ (Newcastle, New South Wales that is) initiated by Marcus Westbury. I mention it briefly in the AR piece, but it’s worth spending a little more time on it.

I’ve been working with Marcus on The Edge project in Brisbane over the last year, and it’s been hugely heartening to watch the project’s development from relatively low-key beginnings to its now-evident success.

In short, the city of Newcastle, NSW is the largest coal port in the world. Yet as the harbour has essentially become a giant open mouth belching coal to China, and people and other business have drifted to the suburbs (an over-simplification, but ...), the historic core of the city has hollowed out, leaving numerous vacant buildings. Heading into the heart of all this, the Renew Newcastle project enabled small businesses, artists, entrepreneurs and various creatives to find a temporary home in these largely unoccupied city centre spaces. By liaising with the building owners, the project found a way of offering super-short-term leases at peppercorn rents in all kinds of pretty vacant spaces. They overlaid a free wi-fi network, enabling basic connectivity, and offered a few other basic amenities. The smart trick of the rolling 30-day lease gave start-ups a contract they could afford to get into, and landlords a secure way of getting them out of it should a better offer arise. Simple.

The project has been achieved without any meaningful funding at all. As a result, the almost derelict city centre is being used again, and the spaces are rapidly being reconfigured, becoming increasingly active, safe, productive.

I can think of few more positive examples of how to quickly make a genuine difference in cities I.e. not just at the surface layers of urban design, as important as that is, or festivals, or marketing, but at the very core of economic, cultural and social sustainability, with all the ensuring knock-on effects for repairing urban fabric and civic confidence. This is why cities exist, after all, and for Marucs and his colleagues to have addressed this aspect directly, with literally no funding, is thoroughly inspirational.

Do read Marcus’s account, written a few months ago now, and this update, which outlines the story. It’s chock-full of potential insight for urban projects elsewhere.

It’ll be interesting to observe how it develops from this point on. When we worked on the Northern Quarter Network about 15 years ago, the development of Network from start-up to ‘matured’ agency was tricky. It’s similar to the growing pains encountered by most start-ups, if they choose to take the ‘growth’ model of development. Renew Newcastle may fade into the woodwork, maintain its resourceful focus, grow to bigger and better things, franchise across different cities, or simply self-destruct (intentionally or not). In some respects this will be dictated by the development of Newcastle itself, but that’s now a symbiotic relationship. Whatever happens, these kind of stages are catalysts - akin to Jaime Lerner’s famous ‘urban acupunctures’ - and in that respect, it’s already done its job.

Since I wrote the piece, I've also discovered the YIMBY movement in Stockholm, which is one of the best things I’ve heard of recently in any field.

Yimby = Yes In My Backyard

This is evidence of what I was trying to get at with the piece below; that we need systems, structures, vocabularies, applications for enabling positive, progressive responses to our urban fabric that are derived from a love for the city.

With that, have a read. (And thanks to Mat Ward at AR for asking me to write it. And then secretly expecting, accounting for - and of course getting - double the word-count he asked for.)

Emergent Urbanism

First published in Architecture Review Australia, November 2009

Given the iSnack 2.0 debacle, it’s not been the best of times for the idea of ‘crowd-sourcing’ things of national value. Yet the potential for direct citizen engagement in the development of our cities continues to inspire discussion and activity nonetheless, with the ‘bottom-up’ processes enabled by the internet’s platforms increasingly seen as the vehicle for such engagement.

Yet when asked to write this article about ‘bottom-up planning’, I was directed towards the recent intervention by the City of Sydney into the planning of various parts of St. Vincent’s Hospital’s extension in Paddington, apparently enabled by the simple transmission of a few renders.

In an article on the matter, Chris Johnson asks whether “the free access to web-based information on planning projects [is] leading to a new democracy in planning?” The answer is of course ‘a qualified yes’, but perhaps more importantly the question should be, “What kind of democracy, and what kind of planning?”

In terms of the first question, much of the debate here focuses on the promise of transparency in such processes, on tools that enable free access to information that was previously hard to come by. Yet, I’d argue that this aspect of access is the least interesting of all the possibilities in internet-enabled bottom-up planning, just as the professional planners of the City of Sydney cannot really be portrayed as the aggregate coalescence of distributed communities of interest that the name implies.

It’s not that citizens don’t need access to information about urban development. We certainly do need more transparency in government, although even that comes with a caveat as to its assumed value. Largely addressing the various government 2.0 programmes around, Lawrence Lessig wrote that, “We are not thinking critically enough about where and when transparency works… The 'naked transparency movement,' as I will call it here, is not going to inspire change. It will simply push any faith in our political system over the cliff.”

We would do well to consider what this means for urban development, which is often teetering on its own cliffs of public opinion. While the St. Vincent’s incident does not appear to be representative of the more shadowy aspects of Australia's urban development, which have often numbed the populace into despairing disinterest, it is already clear that holding back or obfuscating details about urban development, deliberately or otherwise, is not going to work. Trying to get away with it is no longer a plausible strategy. We can look to the winner of the recent GovHack competition in Canberra for an example of the new kinds of application that will deal with this. As one of the event's organisers, John Allsopp, describes: “LobbyClue is an in-depth visualisation of lobbying groups’ relations to government agencies, including tenders awarded, links between the various agencies, and physical office locations.”

You can imagine the shiver down certain spines when that application emerged, and that’s only the start. But while we have to get on the front foot about using such technology to help drive a change in culture, on their own they’re not enough – technology will not directly drive genuine change in attitude, nor should it.

The attitude required for healthy urban development is angled towards positive contributions to the city, not mere exposés of existing bad practice, and here we come to the second question of “What kind of planning?”

Bottom-up implies a more sophisticated engagement with citizens, and from citizens. Genuine engagement in urban development is beyond manipulating dynamic viewsheds, browsing local census data, and poring over a developer’s financial projections. It means opening up the question of what the city is for to its citizens. It means putting many of the tools for design into the hands of citizens, to construct their own everyday city.

One might even argue for the removal of all planning guidelines and structures. After all, most of the world’s great cities are not the product of planning, no matter how enlightened. Certainly some have been well-formed by benevolent dictators or patrons, yet their personality has come from the slow accretion of individual citizens adopting and adapting those spaces, like ficus thriving on béton brut monuments.

While the history of urbanism is essentially one of creative tension between the grands projets of master-planning and the everyday adaptation of citizens, the behaviour of the latter has parallels in other areas, particularly when seen as a system. In his book Emergence, Steven Johnson describes the processes of the adaptive self-organising systems of ants, brains and cities in similar fashion, and although his metaphors are sometimes stretched beyond breaking point, it still might be more productive to describe these ‘bottom-up processes’ as a form of ‘emergent urbanism’. And in this phrase we would seem to have the promise of open-source operating systems such as Linux, or the distributed knowledge production of Wikipedia.

How might this apply to an Australian city?

Sydney in particular is full of holes – tiny pockets of possibility that usually lie fallow. A cursory paw around with Google Earth will reveal gaps in terraces like missing teeth, or small underused car parks, or a disused warehouse, or a well-located but overgrown rail siding, and so on. Every suburb has hundreds of them. Moreover, there are those potential subtractions and adaptations that could reveal yet more space – defunct electricity substations (some of them very beautiful), for instance. The Renew Newcastle programme is a supreme example of creative re-use of such places.

Planning – a fairly cumbersome bureaucratic process – cannot scale down to this level, yet perhaps these are the very places that make a difference to everyday people. The likes of Darling Harbour do not make that difference, for all the millions spent on them. They’re something for the weekend, but not for the week.

Even the world-class re-developments of Carriageworks, Paddington Reservoir and Ballast Point Park fall into this category. No, emergent urbanism is more about knitting together the everyday loose ends in urban fabric, the parts where individuals can coalesce into small groups and make a difference right away, outside of traditional planning processes that are choked by what coders call ‘cruft’ – the extraneous code that creates friction around otherwise elegant structures.

This is where emergent urbanism could be best realised. There are numerous examples of websites and services popping up now that approach this possibility. Some focus on everyday maintenance of the city – such as FixMyStreet or CitySourced. Yet there is potential here for a service which is not simply an advanced way of complaining or reporting to the city, but instead facilitates positive interventions; that would enable people to highlight these small spaces as possibilities for reinvention, suggest some new use cases, even sketch out possible structures using Google’s new Building Maker tool, say. The process might be initiated and enhanced by enabling access to ‘everyday data’ – the kind of pervasive layer of real-time sensor-driven public data that promises to reveal the truly emergent behaviour of many aspects of the city. Citizens will inevitably end up with more data available to them than planners have ever dreamt of, just as they will tend to have a more in-depth understanding of their neighbourhoods, if often unarticulated.

The no-doubt rudimentary nature of the resulting sketches is not the point, at least not yet. When enough people have coalesced around an idea and made investments in emotion, finance and time – in a similar model to the crowd-sourced venture capital service Kickstarter, perhaps – then professionals of various hues can be engaged to more subtly aid the development process.

This is a highly simplistic overview, and crowd-sourcing ideas isn’t a straightforward process, as any Kraft branding executive will tell you (assuming you can still find one to talk to). Equally, urban fabric is not the same as Linux code, just as the difference between a real city and SimCity is almost infinitely vast. Although operating systems can usefully be thought of as immersive environments, compared to the multi-sensory, multi-layered richness of our cities, they are vastly more simplistic.

Yet note the broad potential in tools like Kickstarter or the emerging augmented reality-enabled iPhone apps, and think how they could be applied to those everyday urban spaces where, again, only opportunistic and emergent urbanism can scale down to deliver results.

This even has something of the pre-internet flavours of the kind of Angeleno-led innovative ‘magical urbanism’ that Mike Davis has written about, or the typically mischievous 'Non-Plan' thesis of Banham, Barker, Hall and Price, or the engaged denizens of Jane Jacobs’s Greenwich Village.

But there are a few issues with a fully emergent urbanism, perhaps most vividly conveyed by observing its illogical conclusion. Hong Kong’s now-destroyed Kowloon Walled City is described in Thomas J Campanella’s book The Concrete Dragon as “the closest thing to a truly self-regulating, self-sufficient, self-determining modern city that has ever been built”. While the more romantic urbanists amongst us might love the idea of the Walled City, most of us wouldn’t have lasted more than a day in such an environment.

Another issue is that urban infrastructure has become an ever more important component of a sustainable future, and no such aggregation of individuals is likely to produce energy-efficient transit networks, energy production or land-use with the necessary scale and urgency. Here we will need the guiding hand of the professional and the elected representative, with a reach beyond Facebook, Ning and Twitter.

There is also something worrying in the rhetoric of bottom-up that eternally casts it in opposition to ‘top-down’. While the work of Jacobs was of course profoundly important, it can be argued that much of her legacy now resides not in the open systems of street life she so vividly wrote about, but in a kind of privileged NIMBYism that systematically resists structural change within gentrified neighbourhoods.

In a recent ABC Radio National interview, Michael Sorkin followed a question about Jacobs by describing this “oppositional culture [in which] one of the only ways that citizens can engage planning and other public processes is by their power to say no.”

Sorkin continued, “There must be ways to activate a more positive relationship to planning the environment – rather than simply awaiting decisions by private owners or developers and simply responding to them with our powers to block projects, how much more beautiful it would be if the city were to more rigourously plan its own destiny?”

Indeed there must be ways. In emergent urbanism, we have the seeds of such a beautiful city, yet it can only be realised in constructive tension with its more directed equivalent. Despite the name, bottom-up cannot be seen as an alternative – in opposition – but as something more symbiotic and interdependent. Ironically, we might need professional planning and urban governance to be at the top of its game in order to enable the best in emergent urbanism. This is because both forms of urban behaviour need to be infused with a positive sense of the city. If either side becomes perceived as negative – as now, with the public perception of many official planning and development processes – the other side simply slips into an oppositional stance.

This might well describe our current position, and our cities are left with a million (not in my) backyards locked together in collective stasis, a stand-off of ‘progress versus heritage’, while the nation gets less and less agile in terms of social and economic mobility, and our cities cannot be prepared for the 21st century.

Recent trips to Beijing and Seoul confirmed the necessity for the existence of top-down planning. China and much of South-East Asia is able to move impressively on urban infrastructure in ways that we simply cannot. Yet amidst calmer waters than those of the special economic zones of Shenzhen, Shanghai and New Songdo City, other nations have developed well-considered planning processes, often predicated on well-run open competitions (working as part of the successful team on a recent urban development project in Helsinki, organised and run by the Finnish innovation fund SITRA with real verve, intelligence, and ambition, I was struck by the differences to similar scale projects back home).

While this is partly to do with the mechanics of such processes, more importantly it is to do with the nature of the conversation about cities.

In his book Risk, Dan Gardner discusses how narrative is far more influential than data within a culture. Despite our highly urbanised nation, what is clear is that there are only a few positive narratives around urbanism in Australian cities. For any kind of urbanism to work, emergent or otherwise, Australia needs to discover an affection for cities, and rapidly, such that it can then embrace everything that comes with that: social mobility, cultural progress, sustainable activity, economic resilience, diversity, open-mindedness; civilisation, in short.

Developing an active narrative around urbanism – meaning that the currently polarised camps of densification and suburbanisation can come to the table for a grown-up conversation, for instance – is imperative. Without that, the toxic atmosphere around both top-down and bottom-up planning will continue to bloom and billow like a Sydney dust storm, coating the city in a fine layer of inhibition. Our cities, and our civilisation, cannot afford to slow down at this point. This doesn’t mean they should necessarily continue to grow in raw numbers – although they no doubt will – but they must certainly continue to grow in terms of maturity.

Cities are constantly in tension, and inherently unbalanced systems. That is how they enable change. For successful cities to emerge unscathed from the wheels of creative destruction, an informed, engaged and enabled urbanism needs to inhabit both professional circles and everyday people. While we might be drawn to emergent systems as the other ones are filed in the too-hard basket, it’s in the interlocking totality of this top-down/bottom-up system, suffuse with a positive sense of what a city is, that the answer lies. We have to do nothing less than redesign our culture in order to successfully redesign our cities.

"

URBAN PLANNING: VIDEO :: DRIVING AROUND BRASÍLIA IN 1967 LISTENING TO KRAFTWERK

BRASÍLIA :: «DIE NEUE HAUPTSTADT VON BRASILIEN»

Brasília— that very exotic experiment in tropical modernism — played a huge role in my aesthetic development. I loved looking at (and finding!) photos of Oscar Niemeyer’s buildings when I was developing my passion for architecture.

So, I was particularly thrilled to find this cool video, «DIE NEUE HAUPTSTADT VON BRASILIEN» that gives «faren faren faren» drive, drive, driving on the autobahn a Brazilian twist.

These four minutes and seventeen seconds give us a fascinating glance at the way Brasília looked a few years after the city’s initial wave of infrastructure was built. (The city was founded on 21 April 1960.)

It may be one of the best historical documents we have about the way things looked back then.

I also really like the cool Kraftwerk tune, «Expo 2000» (any song with “expo” in it is sure to be right up my alley). It’s a good mashup with the images.

I wanted to freeze the following images of my City of the Future for future reference. I think they’re great; enjoy them and the video!